This post represents the last of the Road Map series I have shared with over 60,000 readers since introduced in March of 2011 at this humble little site alone. I never would have thought this subject would have attracted so much interest and helped so many over the last three years. Quite frankly I’m astonished at the interest and of course grateful to all the kind words and thoughts so many have shared with me.

This post represents the last of the Road Map series I have shared with over 60,000 readers since introduced in March of 2011 at this humble little site alone. I never would have thought this subject would have attracted so much interest and helped so many over the last three years. Quite frankly I’m astonished at the interest and of course grateful to all the kind words and thoughts so many have shared with me.

The original intent was to share a time tested method to develop, refine, and deliver a professional roadmap producing consistent and repeatable results. This is should be true no matter how deep or how wide or narrow the scope and subject area we are working with. I think I have succeeded in describing the overall patterns employed. The only regret I have is not having enough time and patience with the constraints of this media to dive deeper into some of the more complex and trickier aspects of the delivery techniques. I remain pleased with the results given the little time I have had to share with all of you. And sincerely hope that what has worked for me with great success over the years may help you make your next roadmap better.

This method works well across most transformation programs. As I noted earlier most will struggle to find this in textbooks, class rooms, or in your local book store (I have looked, maybe not hard enough). This method I is based loosely on the SEI-CM IDEAL model used to guide development of long-range integrated planning for managing software process improvement programs. Although the SEI focus is software process improvement the same overall pattern can applied easily to other subject areas like organization dynamics and strategy planning in general.

The Overall Pattern

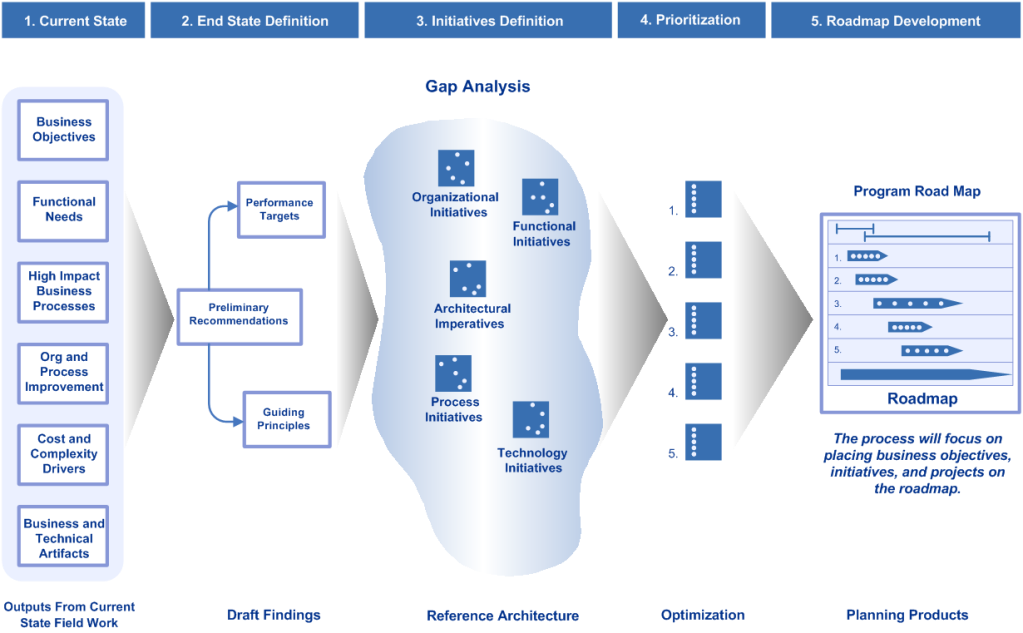

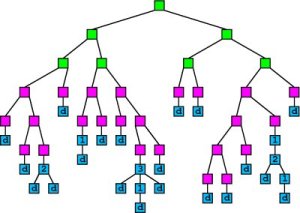

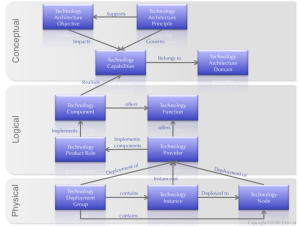

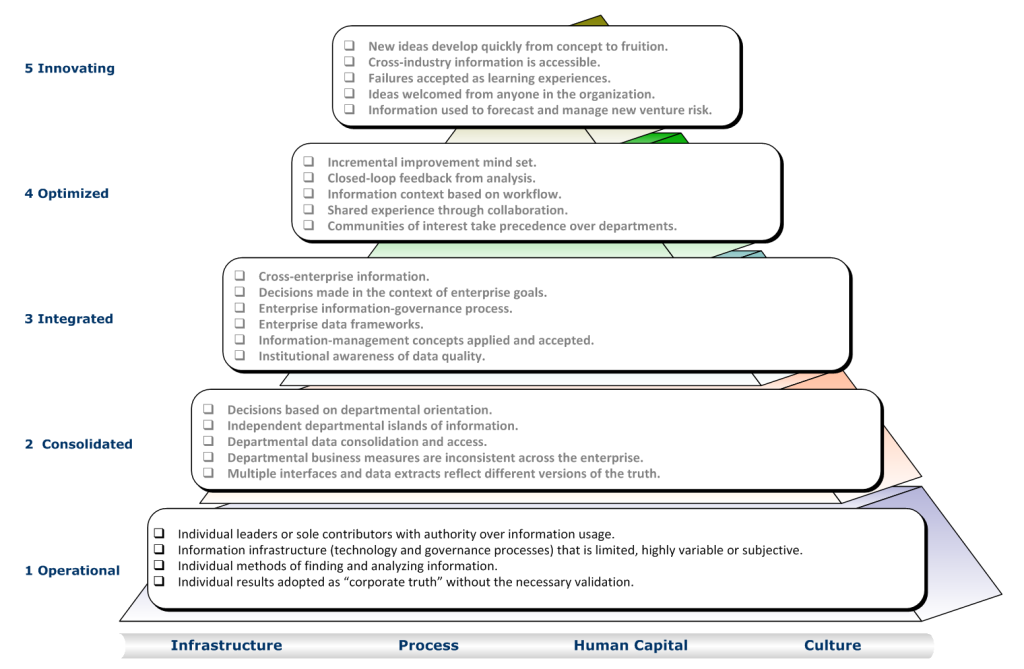

At the risk of over-simplifying things, recall the overall pattern most roadmaps should follow is illustrated in the following diagram.

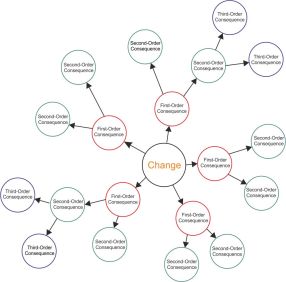

This may look overwhelming at first but represents a complete and balanced approach to understanding what the implications are for each action undertaken across the enterprise as part of a larger program. You can argue (and I would agree) that this may not be needed for simple or relatively straightforward projects. What is more likely in this case is the project or activity we are discussing represents a piece or component part of a much larger initiative and will most certainly not need its’ own roadmap at all. This post is focused on the bigger picture of a collection of projects and activities gathered together to organize and guide multiple efforts in a clear directed manner.

Earlier posts in this series (How to Build a Roadmap) summarized the specific steps required to develop a well thought out road map. The method identified specific actions using an overall pattern all roadmaps should follow. The following steps (and related links to other posts) are required to complete this work:

- Develop a clear and unambiguous understanding of the current state

- Define the desired end state

- Conduct a Gap Analysis exercise

- Prioritize the findings from the Gap Analysis exercise into a series of gap closure strategies

- Discover the optimum sequence of actions (recognizing predecessor – successor relationships)

- Develop and Publish the Road Map

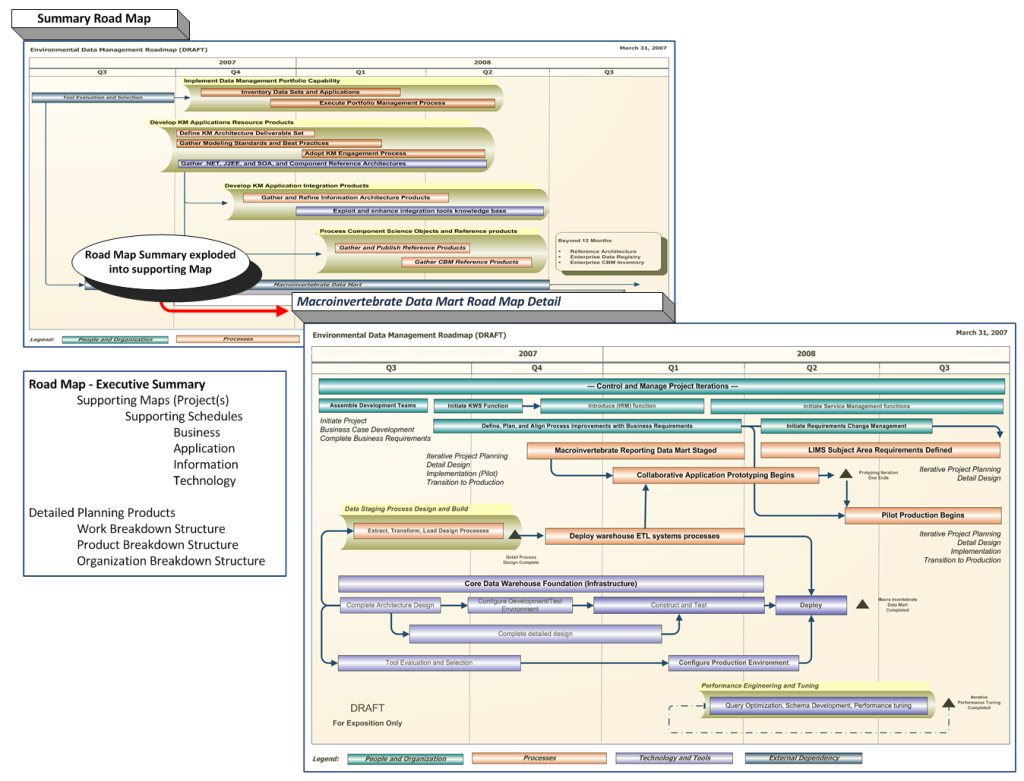

This post wraps up all the hard work to date and assembles the road map to begin sharing the results with stakeholders. Assuming all the prior work is completed, we are now ready to develop and publish the road map. How this is communicated is critical now. We have the facts, we have the path outlined, and we have a defensible position to share with our peers. We have the details readily available to support our position. Now the really difficult exercise rears its ugly head. Somehow, we need to distill and simply our message to what I call the “Duckies and Goats” view of the world. In other words we need to distill all of this work into a simplified yet compelling vision of how we transform an organization, or enabling technology to accomplish what is needed. Do not underestimate the difficulty in this task. After all the hard work put into an exercise like this, the last thing we need to do is to confuse our stakeholders with mind-numbing detail. Yes, we need this for ourselves to exhaust any possibility we have missed something to ensure we haven’t overlooked the obvious because sometimes “when something is obvious, it may be obviously wrong”. So what I recommend is a graphical one or two page view of the overall program where each project is linked to successive layers of detail. Each of these successive layers of detail can also be decomposed further if needed to the detailed planning products and supporting schedules. For an example of this see the accompanying diagram which illustrates the concept..

Develop the Road Map

Develop the Road Map

Armed with the DELTA (current vs. desired end state), the prioritization effort (what should be done), and the optimum sequence (in what order) we can begin to assemble a sensible, defensible road map describing what should be done in what order. Most of the hard work has already been completed so we should be only be concerned at this point with the careful presentation of the results in a way our stakeholders will quickly grasp and understand.

Begin by organizing the high-level tasks and what needs to be accomplished using a relative time scale usually more fine grained for the first set of tasks typically grouped into quarters. Recall each set of recommended initiatives or projects has already been prioritized and sequenced (each of the recommended actions recognize predecessor – successor relationships for example). If this gets too out-of-hand use a simple indexing scheme to order the program using groupings of dimension, priority, sequence, and date related values with your favorite tool of choice. Microsoft Excel pivot tables work just fine for this, and will help organize this work quickly. I use the MindJet MindManager product to organize the results into maps I can prune and graft at will. Using this tool has some real advantages we can use later when we are ready to publish the results and create our detailed program plans.

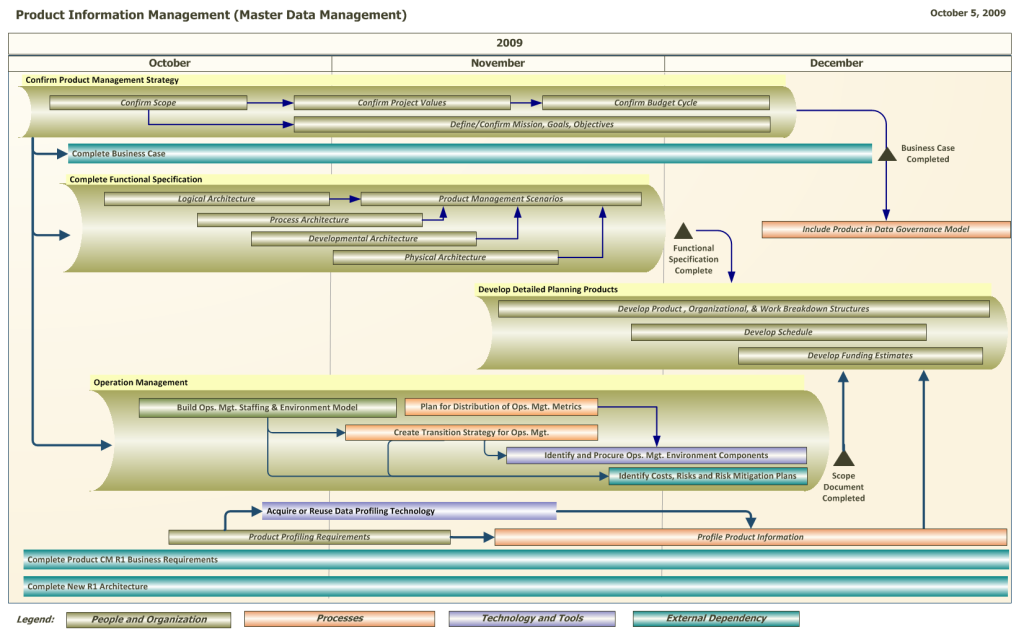

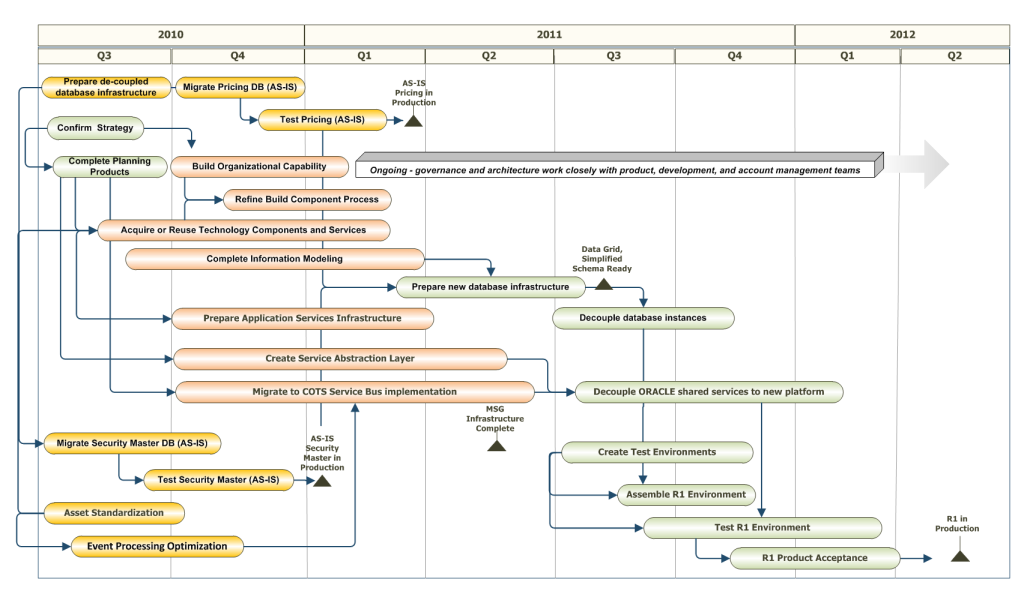

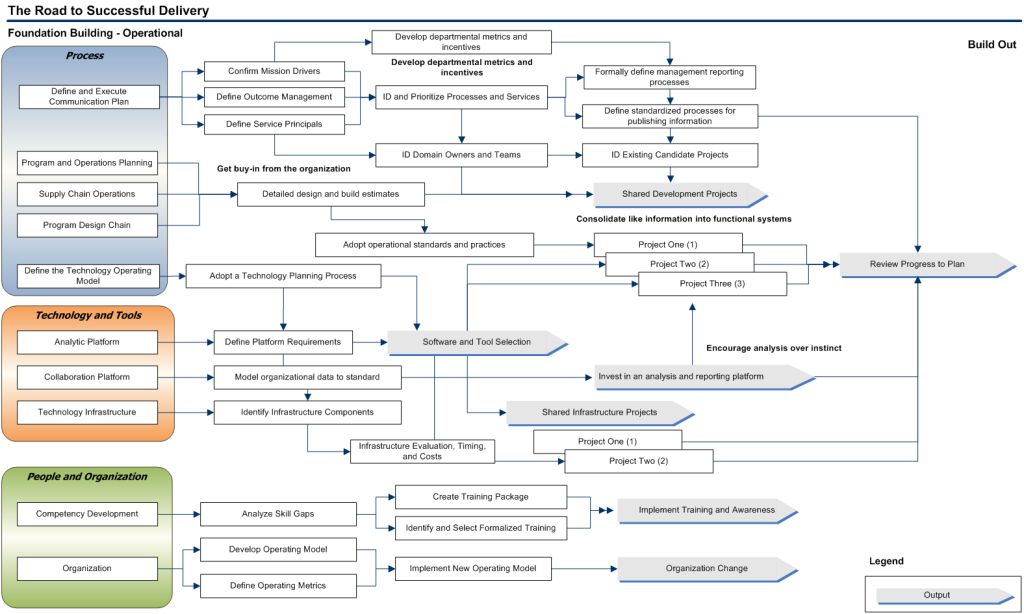

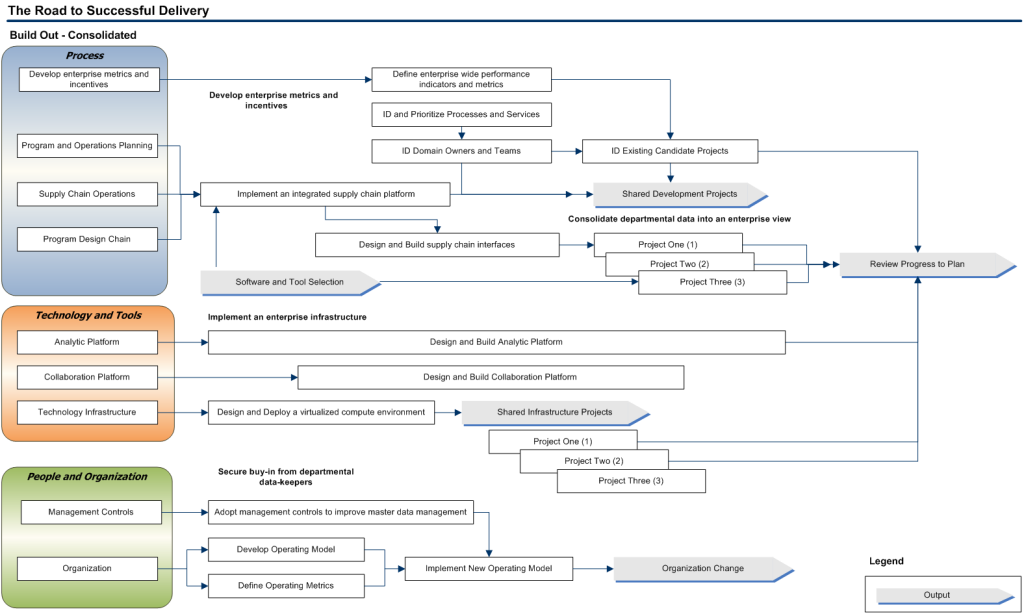

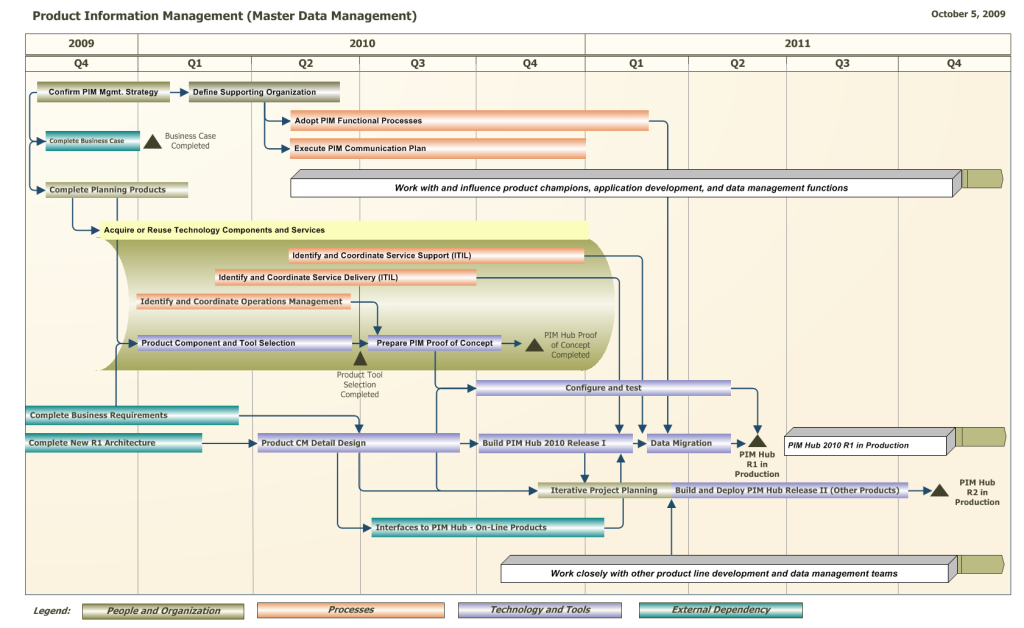

Each project (task(s)) should be is defined by its goals, milestone deliveries, dependencies, and expected duration across relevant dimensions. For example, the dimensions you group by can include People and Organization, Processes, Technology and Tools, and External Dependencies. The following illustrates a high-level view of an example Master Data Management roadmap organized across a multiple year planning horizon.

I think it is a good idea to assemble the larger picture first and then focus on the near term work proposed in the road map. For example, taking the first quarter view of what needs to be accomplished from the executive summary above we can see the first calendar quarter (in this case Q4 2009) of the road map is dedicated to completing the business case, aligning the global strategy, preparing the technical infrastructure for a MDM Product project, and gaining a better understanding of product attribution. The following illustrates the tasks exploded in the summary to the near term map of what is needed in Q4 2009 (the first quarter of this program).

I think it is a good idea to assemble the larger picture first and then focus on the near term work proposed in the road map. For example, taking the first quarter view of what needs to be accomplished from the executive summary above we can see the first calendar quarter (in this case Q4 2009) of the road map is dedicated to completing the business case, aligning the global strategy, preparing the technical infrastructure for a MDM Product project, and gaining a better understanding of product attribution. The following illustrates the tasks exploded in the summary to the near term map of what is needed in Q4 2009 (the first quarter of this program).

Publish the Road Map

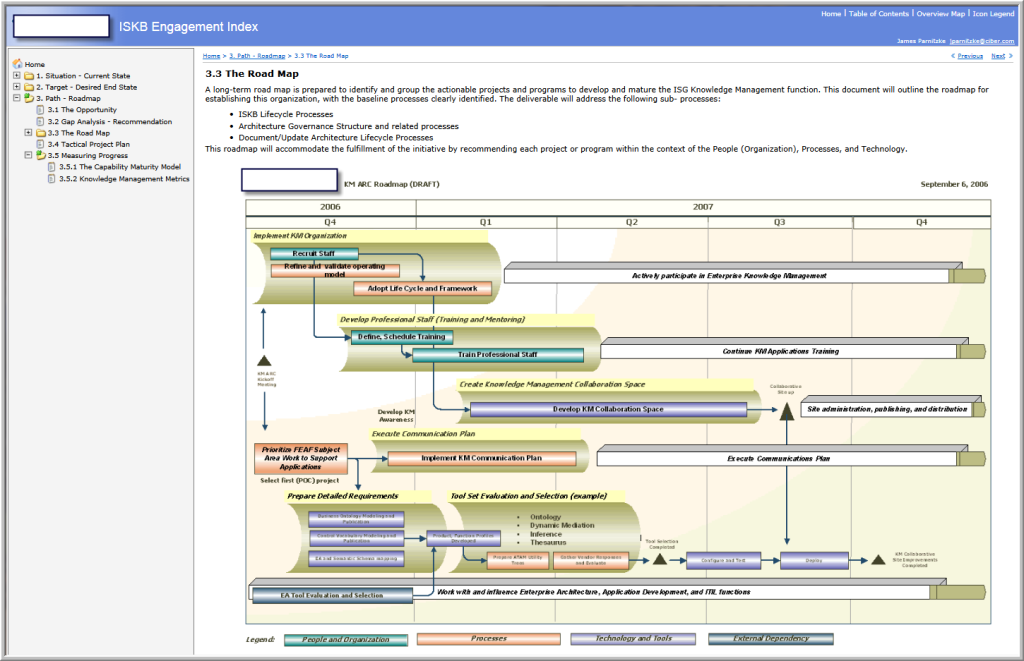

At this stage everything we need is ready for publication, review by the stakeholders, and the inevitable refinements to the plan. I mentioned earlier using MindJet MindManager tool to organize the program initiatives into maps. This tool really comes in handy now to accelerate some key deliverables. Especially useful is the ability to link working papers, schedules, documentation, and any URL hyperlinks needed to support the road map elements. Many still prefer traditional documents (which we can produce with this tool easily) but the real power is quickly assembling the work into a web site that is context aware and a quite powerful way to drill from high level concepts to as much supporting detail as needed. This can easily accessible without the need for source tools (this is a zero footprint solution) by any stakeholder with a browser. The supporting documentation and URL content can be revised and updated easily without breaking the presentation surface when revisions or refinements are made to the original plan. I also use the same tool and content to generate skeleton program project plans for us with MS Project. The plans generated can be further refined and used to organize the detailed planning products when ready. Your Program Management Office (PMO) will love you for this.

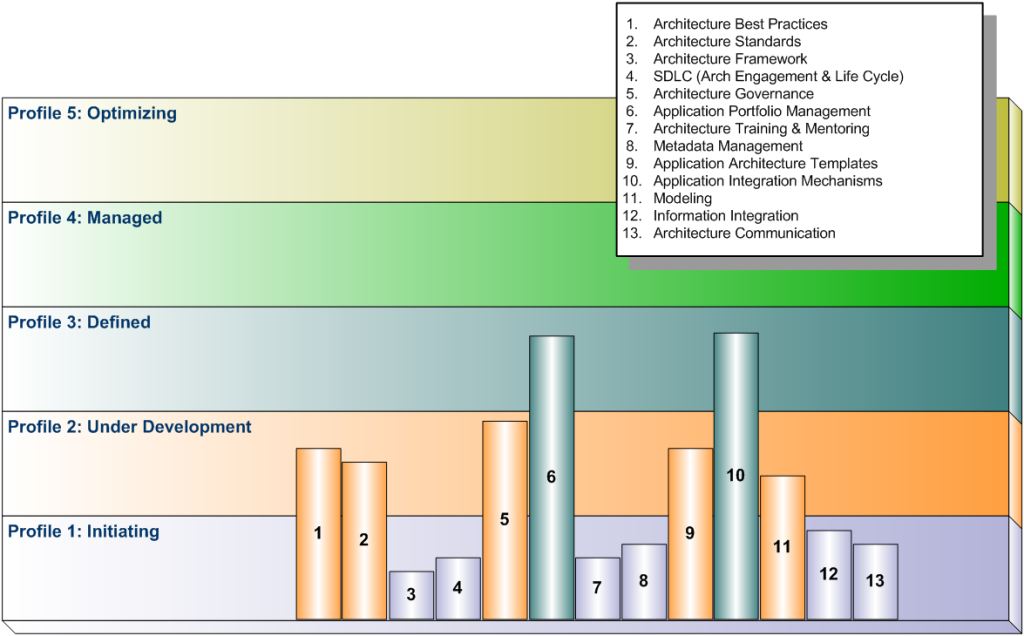

Think you would agree this is an extremely powerful way to organize and maintain a significant amount of related program content to meet the needs of a wide variety of stakeholders. An example of a Road Map web site is illustrated in the snapshot below (note, the client name has been blocked to protect their privacy).

Results

So, we have assembled the roadmap using a basic pattern used across any discipline (business or technology) to ensure an effective planning effort. This work is not an exercise to be taken lightly. We are after all discussing some real world impacts to come up with a set of actionable steps to take along the way that just make sense. Communicating the findings clearly through the road map meets the intent of the program management team and will be used in a variety of different ways. For example beyond the obvious management uses consider the following ways this product will be used.

First, the road map it is a vehicle for communicating the program’s overall intent to interested stakeholders at each stage of its planned execution.

- For downstream designers and implementers, the map provides overall policy and design guidance. The map can be used to establish inviolable constraints (plus exploitable freedoms) on downstream development activities to promote flexibility and innovation if needed.

- For project managers, the road map serves as the basis for a work, product, and organization breakdown structures, planning, allocation of project resources, and tracking of progress by the various teams.

- For technical managers, the road map provides the basis for forming development teams corresponding to the work streams identified.

- For designers of other systems with which this program must interoperate, the map defines the set of operations provided, required, and the protocols that allows the interoperation to take place at the right time.

- For resource managers, testers and integrators, the road map dictates the correct black-box behavior of the pieces that must fit together.

Secondly, the road map can be used as a basis for performing up-front analysis to validate (or uncover deficiencies in) in design decisions and refining or altering those decisions where necessary.

- For the architect and requirements engineers who represent the customer(s), the road map is a framework where architecture as a forum can be used for negotiating and making trade-offs among competing requirements.

- For the architect and component designers, the road map can be a vehicle for arbitrating resource contention and establishing performance and other kinds of run-time resource consumption budgets.

- For those wanting to develop using vendor-provided products from the commercial marketplace, the road map establishes the possibilities for commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) component integration by setting system and component boundaries.

- For performance engineers, the map can provide the formal model guidance that drives analytical tools such as rate schedulers, simulations, and simulation generators to meet expected demands at the right time.

- For development product line managers, the map can help determine whether a potential new member of a product family is in or out of scope, and if out, by how much.

Thirdly, the road map is the first artifact used to achieve program and systems understanding.

- For technical mangers, the map becomes a basis for conformance checking, for assurance that implementations have in fact been faithful to the program and architectural prescriptions.

- For maintainers, the map becomes a starting point for maintenance activities, revealing the relative date and areas when a prospective change is planned to take place.

- For new project members, the map is should be the first artifact for becoming familiar with a program and system’s design intent.

This post wraps up all the hard work to date and assembles the road map to begin sharing with stakeholders impacted by the program as planned. The original intent was to share a time tested method to develop, refine, and deliver a professional roadmap producing consistent and repeatable results. I want to thank all of you embarking down this adventure with me over the last couple years. My sincere hope is that what has worked for me time after time may work just as well for you.